1

Identifying strategies against programmatic fixity, Shepard discusses the concept of ‘generic’ program (pp.23), which seems to express the architectural irrelevance of both form and function in face of immaterial parameters, or situations. Notably, the circumstances of the mass conversion of industrial spaces to lofts were arguably market forces, such as housing shortage and gentrification.

Is it possible to design for a ‘generic’ program that is open to social and cultural dynamics? Where does its indeterminacy lie, if not neither in form or function?

2

We have previously discussed in class that one of the rifts between architecture and technology is that of scale – architecture, in Walter Benjamin’s words, is perceived by the collective, whereas technology tends to operate on a personal level. However, in Sentient City Shepard analyses case studies that use mobile and Internet technologies to shape a “collective representation of urban life” (pp.28).

What is the role of locative media in changing the focus of digital technologies from the individual to the collective? Could they allow urban life not only to be collectively represented in virtual space, but rather collectively produced in real space?

3

McCullough seems to argue for a symbiosis of top-down and bottom-up urban dynamics (pp.198). However, the challenge of integrating the two still remains. IBM’s white paper is eager to provide an easy solution: to parse a vast amount of user-generated data and give them back to the citizens. However, raw data is not information. Meaning relies in interpreting the data through emergent patterns.

Who will have the right to the data? Assuming that raw data is arguably of little use, who will be interpreting this data and why? Is there room for non-corporate or institutional data interpretations in the smart city?

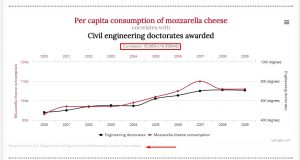

Also, how would the data processing filters be defined? What is put at stake anytime algorithms reach false assumptions, such as those drawn out of proportion in the blog Spurious Correlation (link) ?

The logical fallacies of algorithms