1

Theorizing the electronic object, Anthony Dune elaborates on the differences between the semiotic and the material culture perspective. The understanding of the object as a sign, Dune writes, is tightly connected to its commodification. Challenging the effects of consumerism and marketing strategies on the real, Baudrillard argues that the sign overrides the object itself, crafting a simulation level where it ceases to have any relation to reality. Here, Dune seems to consider material culture as a counter-measure to this condition. Contrary to Baudrilliards’ simulacras, objects approached through a material culture “are firmly grounded in everyday life” (pp.7).

If “the electronic object is (…) on the threshold of materiality” (pp.11) could it actually be an integral part of the simulation? Dune is delineating several design strategies to emphasize its physicality, beyond semiotic or aesthetic considerations. He focuses on the cultural advantages, but does not consider any political implications. In the chapter “Strategy for the Real”, Baudrillard analyzes a common practice of institutions of power, that of “reinjecting realness and referentiality everywhere”(Baudrillard 1981, 374) to make the simulation feel real. In what ways could the reconnect of the electronic object to the world of everyday life be institutionalized and used as a means of control?

2

Mark Weiser describes ubiquitous computing as a condition of embodied virtuality, where our interaction with digital information is “brought out in the physical world” (pp.80). Such an experimental embodied virtuality revolves around the individual. It is not just the computer that is liberated from the confines of the desk, but also the body. It may move freely in space, and the space will ‘automagically’ accommodate it – doors will open, coffee will be made, files will pop up on the meeting screen.

Key prerequisite is for us to establish a degree of familiarity with the tools and processes so that they disappear, literally and metaphorically, in the background. How would we become accustomed to such a strict structure of efficiency and automation? Is really just a matter of effortless repetition and common sense, or does it require technological literacy that can only be achieved through lifelong learning?

It was striking that Weiser considered Artificial Intelligence as irrelevant in ubi-comp (pp.85). How would the environment be always tuned to the needs of each individual, if it is not programmed to sense and learn?

3

William Mitchell dwells on the dematerialization of space as an effect of ICTs. He argues that digitally compressed information makes space irrelevant or unnecessary, as the activities that were traditionally dependent on the production and distribution of printed media become fragments dispersed in the network. In his own words, “all that is solid melts in air” (pp.57).

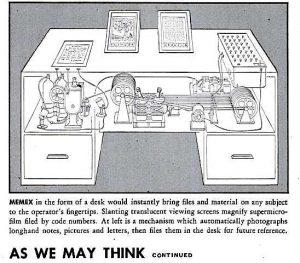

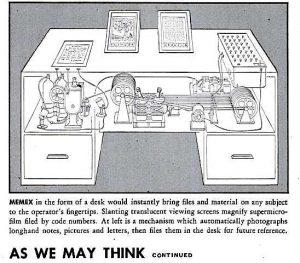

On the other hand, Dune believes that dematerialization is a contingent phenomenon and that, in any case, “the physical can never be completely dismissed” (pp.13). In this light, what role does the architect still have in the material manifestation of information? For instance, if books can be “downloaded to a scholar’s personal workstation in a minute or two” (pp.56) making Vannevar Bush’s memex desk an everyday condition, what relevance does the typology of the library still hold? Is MVRDV’s new library [/link] meaningful in any way, when books are merely treated as means to a form? Note that when form makes the books’ retrieval impossible, the upper shelves are just plastered with images of books.

On the other hand, a prime example of Mitchell’s “virtual museum” that redefines the role of the actual museum, is Cooper Hewitt’s pen [/link].

The materiality of information, as envisioned by Vannevar Bush in 1945:

… and Winy Maas in 2017:

Comments Off on J- Pervasive Computing – pp

“One-time use DVD”

“One-time use DVD”